What Is the Earliest Gestational Age a Baby Can Be Born Without Risk of Major, Lifelong Disability?

- Review

- Open up Access

- Published:

Born As well Presently: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births

Reproductive Wellness volume 10, Article number:S2 (2013) Cite this article

Abstract

This 2d newspaper in the Born Too Before long supplement presents a review of the epidemiology of preterm nascence, and its burden globally, including priorities for activity to amend the data. Worldwide an estimated xi.one% of all livebirths in 2010 were built-in preterm (fourteen.9 million babies born before 37 weeks of gestation), with preterm nascency rates increasing in most countries with reliable trend data. Direct complications of preterm birth account for ane million deaths each year, and preterm birth is a take a chance factor in over 50% of all neonatal deaths. In add-on, preterm birth can result in a range of long-term complications in survivors, with the frequency and severity of agin outcomes rising with decreasing gestational age and decreasing quality of care. The economical costs of preterm birth are large in terms of immediate neonatal intensive care, ongoing long-term complex health needs, as well as lost economic productivity. Preterm nascency is a syndrome with a variety of causes and underlying factors usually divided into spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm births. Consistent recording of all pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirths, and standard application of preterm definitions is important in all settings to accelerate both the understanding and the monitoring of trends. Context specific innovative solutions to prevent preterm birth and hence reduce preterm nativity rates all around the earth are urgently needed. Strengthened data systems are required to fairly track trends in preterm nascency rates and plan effectiveness. These efforts must be coupled with action now to implement improved antenatal, obstetric and newborn intendance to increase survival and reduce disability amongst those born likewise soon.

Declaration

This article is function of a supplement jointly funded by Save the Children'due south Saving Newborn Lives programme through a grant from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and March of Dimes Foundation and published in collaboration with the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and the Earth Health Arrangement (WHO). The original article was published in PDF format in the WHO Report "Born Likewise Soon: the global action study on preterm birth" (ISBN 978 92 four 150343 30), which involved collaboration from more than 50 organizations. The commodity has been reformatted for journal publication and has undergone peer review according to Reproductive Health's standard procedure for supplements and may feature some variations in content when compared to the original report. This co-publication makes the article available to the community in a total-text format.

Why focus on preterm nascence?

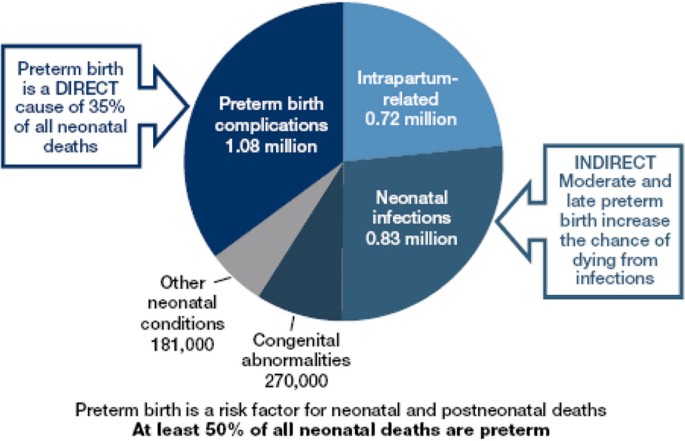

Preterm nascence is a major cause of death and a meaning cause of long-term loss of homo potential amongst survivors all around the world. Complications of preterm birth are the single largest direct crusade of neonatal deaths, responsible for 35% of the world's 3.one million deaths a year, and the second most common crusade of under-five deaths after pneumonia (Effigy 1). In nigh all high- and centre-income countries of the earth, preterm birth is the leading cause of kid death [1]. Being born preterm likewise increases a baby's chance of dying due to other causes, particularly from neonatal infections [2] with preterm nativity estimated to be a risk factor in at to the lowest degree 50% of all neonatal deaths [iii].

Estimated distribution of causes of 3.1 million neonatal deaths in 193 countries in 2010. Source: Updated from Lawn et al., 2005, using data from 2010 published in Liu 50, et al., 2012.

Addressing preterm birth is essential for accelerating progress towards Millennium Development Goal four [4, 5]. In improver to its significant contribution to bloodshed, the event of preterm birth amongst some survivors may go along throughout life, impairing neuro-developmental performance through increasing the risk of cerebral palsy, learning impairment and visual disorders and affecting long-term physical health with a higher adventure of disease [six]. These effects exert a heavy burden on families, society and the health organization (Table 1) [vii, eight]. Hence, preterm birth is one the largest single weather condition in the Global Burden of Disease analysis given the high mortality and the considerable risk of lifelong impairment [9].

Data on preterm birth rates are not routinely collected in many countries and, where bachelor, are frequently not reported using a standard international definition. Time series using consistent definitions are lacking for all but a few countries, making comparison inside and between countries challenging. In high-income countries with reliable data, despite several decades of efforts, preterm nascency rates appear to take increased from 1990 to 2010 [ten–12], although the United States reports a slight decrease in the rates of belatedly preterm nascency (34 to <37 completed weeks) since 2007 [13].

Recent estimates of preterm nativity rates (all live births earlier 37 completed weeks) for 184 countries in 2010 and a time serial for 65 countries with sufficient data suggest that 14.9 1000000 (uncertainty range: 12.three-18.1 meg) babies were born preterm in 2010 [14]. This newspaper reviews the epidemiology of preterm birth, and makes recommendations for efforts to ameliorate the information and apply the data for activeness to accost preterm nascency.

Agreement the information

Preterm birth -- what is it?

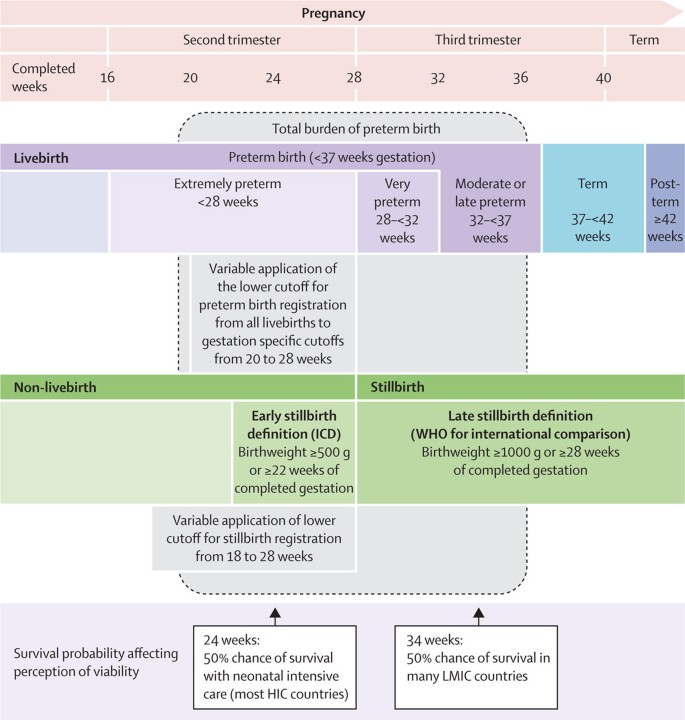

Defining preterm birth

Preterm nascency is divers by WHO as all births earlier 37 completed weeks of gestation or fewer than 259 days since the first day of a woman's last menstrual catamenia [15]. Preterm birth can be further sub-divided based on gestational age: extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28 - <32 weeks) and moderate preterm (32 - <37 completed weeks of gestation) (Figure 2). Moderate preterm birth may exist further split to focus on late pre-term birth (34 - <37 completed weeks). The 37 week cutting off is somewhat arbitrary, and it is now recognized that whilst the risks associated with preterm nativity are greater the lower the gestational age, even babies built-in at 37 or 38 weeks take higher risks than those born at 40 weeks gestation [xvi].

Overview of definitions for preterm nascence and related pregnancy outcomes. Source: Reproduced with permission from Blencowe et al. (2012) National, regional and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the twelvemonth 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 379(9832): 2162-2172.

The international definition for stillbirth charge per unit clearly states to apply stillbirths > ane,000 k or 28 weeks gestation, improving the ability to compare rates beyond countries and times [17, 18]. For preterm birth, International Classification of Illness (ICD) encourages the inclusion of all live births. This definition has no lower boundary, which complicates the comparison of reported rates both between countries and inside countries over time since perceptions of viability of extremely preterm babies change with increasingly sophisticated neonatal intensive care, and some countries only include live births after a specific cut-off, for example, 22 weeks. In addition, other reports utilize non-standard cutting-offs for upper gestational age (e.g., including babies born at up to 38 completed weeks of gestation).

In many loftier-and eye-income countries, the official definitions of live nascency or stillbirth have changed over fourth dimension. Even without an explicit lower gestational age cut-off in national definitions, the medical intendance given and whether or not birth and death registration occurs may depend on these perceptions of viability [19, xx]. Hence, fifty-fifty if no "official" lower gestational age cut-off is specified for recording a live birth, misclassification of a livebirth to stillbirth is more than common if the medical team perceives the baby to be extremely preterm and thus less likely to survive [20]. 80 percent of all stillbirths in loftier-income countries are born preterm, accounting for 5% of all preterm births. Counting just live births underestimates the true burden of preterm nascency [21, 22].

In add-on to the definition and perceived viability upshot, some reports include only singleton live births, complicating comparison even farther. From a public health perspective and for the purposes of policy and planning, the full number of preterm births is the measure of involvement.

Preterm birth - why does it occur?

Preterm birth is a syndrome with a diversity of causes which can be classified into two broad subtypes: (i) spontaneous preterm birth (spontaneous onset of labour or following prelabour premature rupture of membranes (pPROM)) and (ii) provider-initiated preterm birth (defined as induction of labor or elective caesarean birth earlier 37 completed weeks of gestation for maternal or fetal indications (both "urgent" or "discretionary"), or other non-medical reasons) (Table ii) [23].

Spontaneous preterm birth is a multi-factorial process, resulting from the interplay of factors causing the uterus to change from quiescence to active contractions and to birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation. The precursors to spontaneous preterm birth vary by gestational historic period [24], and social and environmental factors, simply the cause of spontaneous preterm labor remains unidentified in up to half of all cases [25]. Maternal history of preterm nativity is a strong chance factor and well-nigh likely driven past the interaction of genetic, epigenetic and environmental risk factors [26]. Many maternal factors accept been associated with an increased take a chance of spontaneous preterm birth, including young or advanced maternal age, short inter-pregnancy intervals and low maternal body mass index [27, 28].

Some other important gamble factor is uterine over amplification with multiple pregnancy. Multiple pregnancies (twins, triplets, etc.) behave almost 10 times the adventure of preterm nativity compared to singleton births [29]. Naturally occurring multiple pregnancies vary amidst ethnic groups with reported rates from ane in forty in West Africa to 1 in 200 in Japan, but a large contributor to the incidence of multiple pregnancies has been ascension maternal age and the increasing availability of assisted conception in high-income countries [30]. This has led to a large increment in the number of births of twins and triplets in many of these countries. For example, England and Wales, France and the United States reported l to 60% increases in the twin rate from the mid-1970s to 1998, with some countries (east.grand. South korea) reporting even larger increases [31]. More recent policies, limiting the number of embryos transferred during in vitro fecundation may have begun to reverse this tendency in some countries [32], while others proceed to study increasing multiple birth rates [33, 34].

Infection plays an of import function in preterm birth. Urinary tract infections, malaria, bacterial vaginosis, HIV and syphilis are all associated with increased gamble of preterm nascency [35]. In improver, other conditions take more than recently been shown to be associated with infection, e.g., "cervical insufficiency" resulting from ascending intrauterine infection and inflammation with secondary premature cervical shortening [36].

Some lifestyle factors that contribute to spontaneous preterm nascency include stress and excessive physical work or long times spent standing [28]. Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption as well every bit periodontal disease likewise have been associated with increased risk of preterm nascency [35].

Preterm nascency is both more common in boys, with around 55% of all preterm births occurring in males [37], and is associated with a higher risk of dying when compared to girls born at a similar gestation [38]. The role of ethnicity in preterm birth (other than through twinning rates) has been widely debated, but evidence supporting a variation in normal gestational length with ethnic grouping has been reported in many population-based studies since the 1970s [39]. While this variation has been linked to socioeconomic and lifestyle factors in some studies, recent studies suggest a role for genetics. For example, babies of blackness African ancestry tend to be born earlier than Caucasian babies [24, forty]. However, for a given gestational age, babies of blackness African ancestry have less respiratory distress [41], lower neonatal mortality [42] and are less likely to require special care than Caucasian babies [24]. Babies with congenital abnormalities are more probable to be built-in preterm, but are frequently excluded from studies reporting preterm birth rates. Few national-level data on the prevalence of the risk factors for preterm birth are bachelor for modelling preterm birth rates.

The number and causes of provider-initiated preterm birth are more variable. Globally, the highest burden countries accept very low levels due to lower coverage of pregnancy monitoring and low caesarean birth rates (less than 5% in most African countries). Nevertheless, in a recent study in the United States, more than one-half of all provider-initiated pre-term births at 34 to 36 weeks gestation were carried out in absence of a stiff medical indication [43]. Unintended preterm birth besides tin can occur with the elective delivery of a babe thought to exist term due to errors in gestational age assessment [44]. Clinical conditions underlying medically-indicated preterm nativity can be divided into maternal and fetal of which severe preeclampsia, placental abruption, uterine rupture, cholestasis, fetal distress and fetal growth restriction with aberrant tests are some of the more important straight causes recognized [39]. Underlying maternal conditions (e.g., renal disease, hypertension, obesity and diabetes) increase the hazard of maternal complications (e.g., preeclampsia) and medically-indicated preterm nascence. The worldwide epidemic of obesity and diabetes is, thus, probable to become an increasingly important contributor to global preterm birth. In one region in the United Kingdom, 17% of all babies born to diabetic mothers were preterm, more than than double the charge per unit in the general population [24]. Both maternal and fetal factors are more frequently seen in pregnancies occurring after assisted fertility treatments, thus increasing the risk of both spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm births [44, 45].

Differentiating the causes of preterm birth is particularly of import in countries where cesarean birth is mutual. Nearly 40% of preterm births in French republic and the United States were reported to be provider-initiated in 2000, compared to only over twenty% in Scotland and the netherlands. The levels of provider-initiated preterm births are increasing in all these countries in role due to more aggressive policies for caesarean section for poor foetal growth [46, 47]. In the United States, this increase is reported to be at least in part responsible for the overall increase in the preterm nascency rate from 1990 to 2007 and the pass up in perinatal mortality [39]. No population-based studies are available from low- or centre-income countries. However, of the babies born preterm in tertiary facilities in low- and center-income countries, the reported proportion of preterm births that were provider-initiated ranged from around 20% in Sudan and Thailand to nearly 40% in 51 facilities in Latin America and a education hospital in Ghana [48–51]. Withal, provider-initiated preterm births volition represent a relatively smaller proportion of all preterm births in these countries where access to diagnostic tools is limited. These pregnancies, if not delivered electively, volition follow their natural history, and may frequently end in spontaneous preterm birth (live or stillbirth)[52].

Preterm birth--how is it measured?

There are many challenges to measuring preterm birth rates that have inhibited national data interpretation and multi-land assessment. In addition to the variable awarding of the definition, the varying methods used to measure gestational age and the differences in case ascertainment and registration complicate the interpretation of preterm birth rates across and within nations.

Assessing gestational age

Measurement of gestational age has changed over time. As the dominant effect of gestational age on survival and long-term impairment has become apparent over the terminal 30 years, perinatal epidemiology has shifted from measuring birthweight alone to focusing on gestational age. Notwithstanding, many studies, even of related pregnancy outcomes, continue to omit central measures of gestational age. The most authentic "golden standard" for assessment is routine early ultrasound assessment together with foetal measurements, ideally in the first trimester. Gestational assessment based on the date of last menstrual flow (LMP) was previously the most widespread method used and remains the only bachelor method in many settings. It assumes that formulation occurs on the same solar day as ovulation (xiv days after the onset of the LMP). It has low accurateness due to considerable variation in length of menstrual cycle among women, formulation occurring up to several days after ovulation and the recall of the date of LMP being subject field to errors [53]. Many countries at present use "best obstetric estimate," combining ultrasound and LMP as an approach to gauge gestational historic period. The algorithm used tin can accept a big affect on the number of preterm births reported. For example, a big written report from a Canadian education hospital found a preterm rate of 9.1% when assessed using ultrasound alone, compared to 7.eight% when using LMP and ultrasound [31].

Whatever method using ultrasound requires skilled technicians, equipment and for maximum accuracy, get-go-trimester antenatal clinic attendance. These are not mutual in depression-income gear up tings where the majority of preterm births occur. Alternative approaches to LMP in these set tings include clinical cess of the newborn subsequently birth, fundal height or birthweight as a surrogate. While birthweight is closely linked with gestational historic period, it cannot be used interchangeably since there is a range of "normal" birthweight for a given gestational age and gender. Birthweight is likely to overestimate preterm birth rates in some settings, particularly in South asia where a high proportion of babies are small for gestational historic period.

Bookkeeping for all births

The recording of births and deaths and the likelihood of active medical intervention after preterm birth are affected by perceptions of viability and social and economic factors, specially in those born close to the lower gestational age cut-off used for registration. Any baby showing signs of being live at birth should exist registered every bit a livebirth regardless of the gestation [54]. The registration thresholds for stillbirths vary between countries from 16 to 28 weeks, and nether-registration of both live and stillbirths close to the registration boundary is well documented [55]. The cut-off for viability has changed over time and varies across settings, with babies born at 22 to 24 weeks receiving total intensive care and surviving in some high-income countries, whilst babies born at upward to 32 weeks gestation are perceived equally non-feasible in many low-resources settings. An instance of this reporting bias is seen in loftier-income settings where the increase in numbers of extremely preterm (<28 weeks) births registered is likely to be due to improved example ascertainment rather than a genuine increment in preterm births in this group [56] and three community cohorts from Southern asia with high overall preterm birth rates of 14 to 20%, merely low proportions (2%) of extremely preterm births (<28 weeks) compared to the proportion from pooled datasets from developed countries (5.3%). In addition, even where intendance is offered to these very preterm babies, intensive care may be rationed [57, 58].

Other cultural and social factors that have been reported to bear upon abyss of registration include provision of maternity benefits for any birth subsequently the registration threshold, the need to pay burial costs for a registered birth but not for a miscarriage and increased hospital fees following a nativity compared to a miscarriage [59]. In low-income settings, a alive preterm birth may be counted every bit a stillbirth due to perceived non-viability or to "protect the mother" [55].

The definition of preterm nativity focuses on live-born babies only. Counting all preterm births, both alive and stillborn, would be preferable to improve comparability specially given stillbirth/livebirth misclassification. An increasing proportion of all preterm infants born volition exist stillborn with decreasing gestational historic period. The pathophysiology is like for live and stillbirths; thus, for the truthful public health burden, information technology is essential to count both preterm babies born alive and all stillbirths [23]. Until these classification differences based on method (Table 3), lower gestational age cutting-offs for registration of preterm nativity, the use of singleton versus all births (including multiples), the inclusion of live births versus full births (including alive and stillbirths) and instance ascertainment have been resolved, circumspection needs to exist applied when interpreting regional and temporal variations in preterm birth rates.

Using the data for activeness

Preterm birth rates--where, and when?

Global, regional and national variation of preterm birth for the year 2010

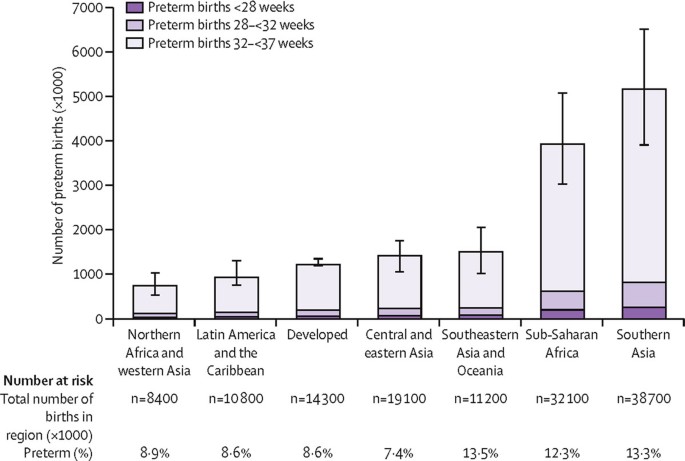

New WHO estimates of global rates of preterm births indicate that of the 135 million live births worldwide in 2010, xiv.9 million babies were born preterm, representing a preterm birth charge per unit of 11.1% [14]. Over 60% of preterm births occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern asia where 9.1 meg births (12.viii%) annually are estimated to be preterm (Figure three). The high absolute number of preterm births in Africa and Asia are related, in part, to high fertility and the large number of births in those two regions in comparison to other parts of the world.

Preterm births by gestational age and region for the twelvemonth 2010. Based on Millennium Evolution Goal regions. Source: Reproduced with permission from Blencowe et al. (2012) National, regional and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 379(9832): 2162-2172.

The variation in the rate of preterm nascence amid regions and countries is substantial and yield a different picture to other weather condition in that some loftier-income countries accept very high rates. Rates are highest on average for low-income countries (xi.eight%), followed by lower middle-income countries (11.3%) and everyman for upper centre- and high-income countries (nine.iv% and 9.3%). All the same, relatively high preterm birth rates are seen in many individual loftier-income countries where they contribute essentially to neonatal mortality and morbidity. Of the 1.two million preterm births estimated to occur in high-income regions, more 0.5 million (42%) occur in the United States. The highest rates past Millennium Development Goal Regions [sixty] are plant in Southeastern and Southern asia where 13.4% of all alive births are estimated to be preterm (Figure 3).

The dubiety ranges in Effigy 3 are indicative of some other problem -- the huge information gaps for many regions of the globe. Although these data gaps are particularly great for Africa and Asia, at that place also are gaps in data from loftier-income countries. While information on preterm birth-associated bloodshed are lacking in these settings, worldwide there are almost no data currently on acute morbidities or long-term impairment associated with prematurity, thus preventing even the about basic assessments of service needs.

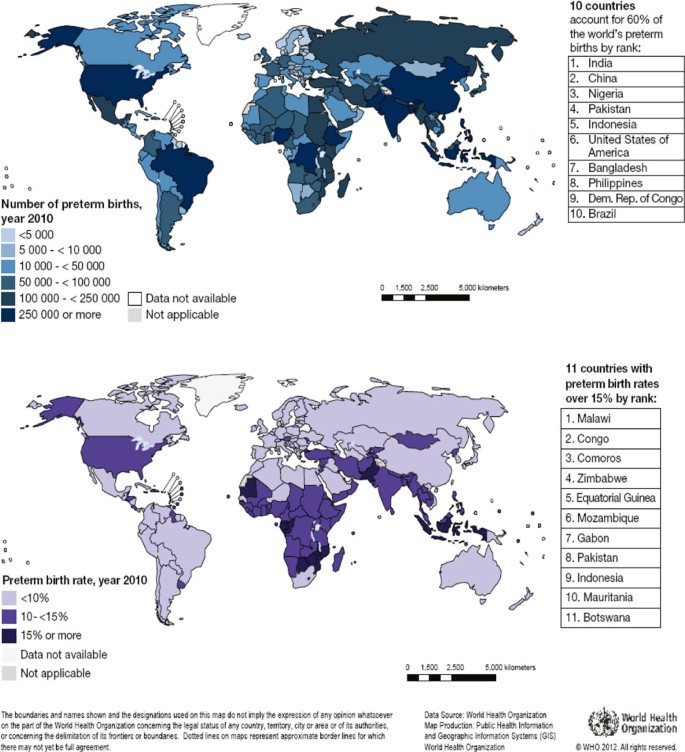

The maps in Effigy iv depict preterm nativity rates and the absolute numbers of preterm nascency in 2010 by land. Estimated rates vary from around 5 in several Northern European countries to 18.1% in Malawi. The estimated preterm birth rate is less than 10% in 88 countries, whilst 11 countries have estimated rates of 15% or more than (Effigy 4). The 10 countries with the highest numbers of estimated preterm births are India, Cathay, Nigeria, Pakistan, Indonesia, United States, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Democratic republic of the congo and Brazil (Figure 4). These ten countries account for 60% of all preterm births worldwide.

Preterm births in 2010. Source: Blencowe, H., et al. (2012) Chapter 2: xv one thousand thousand preterm births: Priorities for activity based on national, regional and global estimates. In Born Too Before long: the Global Activity Report on Preterm Birth. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/borntoosoon_chapter2.pdf 2012 [79]. Not applicable = non WHO Members State.

Mortality rates increase with decreasing gestational historic period, and babies who are both preterm and small for gestational historic period are at even college chance [61]. Babies built-in at less than 32 weeks stand for about 16% of all preterm births [14]. Beyond all regions, bloodshed and morbidity are highest amongst those babies although improvements in medical care take led to improved survival and long-term outcomes among very and extremely preterm babies in high-income countries [62]. In 1990, around 60% of babies born at less than 28 weeks gestation survived in high-income settings, with approximately two-thirds surviving without impairment [63]. In these high-income countries, near 95% of those built-in at 28 to 32 weeks survive, with more than 90% surviving without impairment. In contrast, in many depression-income countries, only 30% of those born at 28 to 32 weeks survive, with almost all those built-in at <28 weeks dying in the showtime few days of life. In all settings, these very or extremely preterm babies account for the majority of deaths, specially in low-income countries where fifty-fifty simple care is lacking [64].

Preterm births fourth dimension trends 1990 to 2010

Absolute numbers and rates of preterm birth for 65 countries in Europe, the Americas and Australasia from 1990 to 2010 for these countries suggest an increasing burden of preterm birth [five]. This increment is partly explained past an increase in preterm births occurring at 32 to <37 weeks (late and moderate preterm) reported over the past decades in some countries [65]. Despite a reduction in the number of alive births, the estimated number of preterm births in these countries increased from 2.0 million in 1990 to nigh 2.2 million in 2010 [fourteen]. Preterm nascency rate trends for low- and middle-income countries suggest an increase in some countries (east.g., Red china) and some regions (e.g., South Asia) but given changes in the data type and the measurement of gestational age, these remain uncertain.

Priority policy and plan actions based on the information

In 2010, approximately xv million babies were born preterm, and more 1 1000000 died due to complications in the first calendar month of life, more from indirect furnishings, and millions have a lifetime of impairment. The brunt of preterm birth is highest in low-income countries, specially those in Southern asia. Yet unlike many other global health issues, preterm birth is truly a global trouble with a loftier brunt being institute in loftier-income countries as well (e.g. the United States where almost one in 8 babies is preterm). However, while the run a risk of preterm birth is high for both the poorest and the richest countries, in that location exists a major survival gap in some regions for babies who are preterm. In high-income settings, half of babies born at 24 weeks may survive, simply in depression-income settings half of babies built-in at 32 weeks still dice due to a lack of bones care [64].

Preterm birth rates appear to be increasing in well-nigh of the countries where data are available. Some of this increase may exist accounted for by improved registration of the most preterm babies associated with increased viability and past improved gestational assessment, with change to near universal ultrasound for dating pregnancies in these settings. It may, nonetheless, correspond a true increase. Possible reasons for this include increases in maternal historic period, admission to infertility treatment, multiple pregnancies and underlying health problems in the female parent, peculiarly with increasing age of pregnancy and changes in obstetric practices with an increase in provider-initiated preterm births in moderate and late preterm infants who would not take otherwise been born preterm [46]. In the 1980s and 1990s, the increases seen in many high-income countries were attributed to higher multiple gestation and preterm birth rates amid assisted conceptions after treatment for sub-fertility. Recent changes in policies limiting the number of embryos that tin be implanted take led to a reduction in preterm births due to assisted fertility treatments in many countries [63]. However, in many middle-income regions with newer, relatively unregulated assisted fertility services, a like increase may exist seen if policies to annul this are not introduced and adhered to. A reduction in preterm nascence was reported from the 1960s to 1980s in a few countries (eastward.g. Finland, France, Scotland), and this was attributed, in part, to improved socioeconomic factors and antenatal care. For the majority of countries in low- and middle-income regions, it is not possible to estimate trends in preterm nativity over time every bit at that place are not sufficient data to provide reliable evidence of a time trend for preterm nascence overall. Some countries in some regions (e.g. South and East asia) have information suggesting possible increases in preterm nascency rates over fourth dimension, but this may represent measurement artifact due to increases in data and data reliability.

Distinguishing spontaneous and provider-initiated preterm birth is of importance to programs aiming to reduce preterm nativity. For spontaneous preterm births, the underlying causes demand to be understood and addressed while in the example of provider-initiated preterm births both the underlying weather (e.k. preeclampsia) and obstetric policies and practices require assessment and to be addressed [66, 67].

The proportion of neonatal deaths attributed to preterm births is inversely related to neonatal mortality rates, because in countries with very high neonatal mortality, more deaths occur due to infections such as sepsis, pneumonia, diarrhea and tetanus also equally to intrapartum-related "birth asphyxia" [2]. However, although the proportion of deaths due to preterm birth is lower in low-income countries than in high-income countries, the crusade-specific rates are much college in low- and eye-income than in high-income countries. For example, in Afghanistan and Somalia, the estimated cause-specific rate for neonatal deaths direct due to preterm birth is 16 per i,000 compared to Japan, Norway and Sweden where information technology is nether 0.5 per 1,000. This is due to the lack of even simple care for premature babies resulting in a major survival gap for babies depending on where they are born [64].

Preterm nascence tin issue in a range of long-term complications in survivors, with the frequency and severity of agin outcomes ascent with decreasing gestational age and decreasing quality of care (Table i). Most babies born at less than 28 weeks need neonatal intensive care services to survive, and nigh babies 28 to 32 weeks will demand special newborn intendance at a minimum. The availability and quality of these services are not yet well established in many low- and middle-income countries. Many middle-income countries, currently scaling upward neonatal intensive care, are just beginning to experience these long-term consequences in survivors. 43% of the estimated 0.9 million preterm babies surviving with neurodevelopmental impairment are from middle income countries [8]. These effects are most marked amongst survivors born extremely preterm; however, there is increasing bear witness that all premature babies regardless of gestational age are at increased risk. The vast bulk (84%) of all preterm births occur at 32 to 36 weeks. Nigh of these infants will survive with adequate supportive intendance and without needing neonatal intensive intendance. Still, even babies built-in at 34 to 36 weeks have been shown to accept an increased chance of neonatal and infant death when compared with those born at term and contribute chiefly to overall infant deaths [68]. Babies born at 34 to 36 weeks also experience increased rates of short-term morbidity associated with prematurity (e.thousand., respiratory distress and intraventricular hemorrhage) than their peers built-in at term [69–71]. In the longer term, they accept worse neurodevelopmental and schoolhouse performance outcomes and increased run a risk of cerebral palsy [72, 73]. On a global level, given their relatively larger numbers, babies born at 34 to 36 weeks are probable to have the greatest public health impact and to be of the most importance in the planning of services (due east.g., training community health workers in Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC), essential newborn care and special care of the moderately preterm babe) [64].

We have highlighted the differences in preterm birth rates among countries, but marked disparities are besides present inside countries. For example, in the U.s.a. in 2009, reported preterm nascency rates were as loftier as 17.v% in black Americans, compared to just 10.9% in white Americans, with rates varying from around 11 to 12% in those xx to 35 years of age to more than than 15% in those under age 17 or over 40 [13]. Disparities within countries need to be improve understood in society to place high-risk groups and better care.

The economic costs of preterm birth are large in terms of the immediate neonatal intensive intendance and ongoing long-term complex health needs frequently experienced. These costs, in improver, are likely to rise as premature babies increasingly survive at earlier gestational ages in all regions. This survival also volition upshot in the increased demand for special education services and associated costs that will place an boosted burden on affected families and the communities in which they alive [74]. An increased awareness of the long-term consequences of preterm birth (at all gestational ages) is required to fashion policies to support these survivors and their families as part of a more than generalised comeback in quality of care for those with disabilities in any given country. In many heart-income countries, preterm nascency is an of import cause of inability. For example, a tertiary of all children under 10 in schools for the visually dumb in Vietnam and more than twoscore% of nether-5's in similar schools in United mexican states have incomprehension secondary to retinopathy of prematurity [75, 76].

Actions to amend the data

The estimates from the Built-in Too Soon report represent a major step forward in terms of presenting the showtime-ever national preterm birth estimates [77]. However, activeness is required to amend the availability and quality of data from many countries and regions and, where data are existence collected and analysed, to improve consistency among countries. These are vital next steps to monitor the progress of policies and programs aimed at reducing the large cost of preterm nativity (Table 4). Efforts in every country should be directed to increasing the coverage and systematic recording of all preterm births in a standard reporting format. Standardisation of the definition in terms of both the numerator (the number of preterm births) and the denominator (the number of all births) is essential if trends and rankings are to be truly comparable. Collecting data on both live and stillbirths separately will permit further quantification of the true burden, while data focusing on alive births only are required for monitoring of neonatal and longer-term outcomes. These estimates indicate the large burden amidst alive-born babies. However, in developed countries with available data, between v and ten% of all preterm births are stillbirths, and the figure may be higher in countries with lower levels of medicallyinduced preterm birth. Distinguishing between alive births and stillbirths may vary depending on local policies, the availability of intensive intendance and perceived viability of babies who are extremely preterm. If estimates for live-built-in preterm babies were linked to estimates for stillbirths, this would meliorate tracking among countries and over time. Achieving consensus around the dissimilar types of preterm birth and comparable case definitions, whilst challenging, are required where resource allow to further sympathise the circuitous syndrome of preterm birth [23].

In many depression- and middle-income countries without wide-scale vital registration, no nationally representative data are available on rates of preterm nascency. Substantial investment and attention are required to improve vital registration systems and to account for all nativity outcomes [78]. In the meantime, the amount of population-based data bachelor in high-brunt countries could be dramatically increased to ameliorate inform futurity estimates and monitor time trends if data on preterm birth rates were able to be included in nationally representative surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), but this will require developing, testing and training in the utilize of preterm-specific survey-based tools which are non currently available. The advent of inexpensive portable ultrasound machines makes inclusion of routine early on ultrasound scans in demographic surveillance sites or representative cohorts a promising route to increase information availability in these settings in the short term. Innovation for simpler, low-cost, sensitive and specific tools for assessing gestational age could better both the coverage and quality of gestational age cess. Data from hospital-based information systems would as well be helpful, but potential option and other biases must be taken into account. Simpler standardized tools to assess astute and long-term morbidities-associated preterm nativity also are critically important to inform program quality comeback to reduce the proportion of survivors with preventable impairment.

Determination

There are sufficient data to justify activity now to reduce this large burden of 15 million preterm births and more than i million neonatal deaths. Innovative solutions to forbid preterm nascency and hence reduce preterm nativity rates all around the world are urgently needed. This also requires strengthened data systems to fairly track trends in preterm birth rates and program effectiveness. These efforts must exist coupled with activity now to implement improved antenatal, obstetric and newborn intendance to increase survival and reduce disability amongst those built-in as well presently. These are reviewed further in the following papers in this supplement.

Funding

HB and SC were funded through a grant from the Pecker & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Child Wellness Epidemiology Reference Group. JL and MK were funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation though Save the Children's Saving Newborn Lives program.

Abbreviations

- pPROM:

-

prelabour premature rupture of membranes

- WHO:

-

World Wellness Organisation.

References

-

Liu L, Johnson H, Cousens South, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn J, Ruden I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Mengying L: Global, regional and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. The Lancet. 2012, 379: 2151-2161. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-i.

-

Backyard JE, Cousens S, Zupan J: 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why?. Lancet. 2005, 365: 891-900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5.

-

Lawn JE, Kerber G, Enweronu-Laryea C, Cousens S: 3.half dozen million neonatal deaths - what is progressing and what is non?. Semin Perinatol. 2010, 34: 371-386. 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.09.011.

-

Millennium Evolution Goals Indicators. [http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Default.aspx]

-

Howson CP, Kimmey MV, McDougall L, Lawn JE: Born Likewise Soon: Preterm birth matters. Reprod Health. 2013, 10 (Suppl 1): S1-x.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S1.

-

Rogers LK, Velten M: Maternal inflammation, growth retardation, and preterm birth: insights into adult cardiovascular disease. Life Sci. 2011, 89: 417-421. 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.07.017.

-

Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. [http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2006/Preterm-Birth-Causes-Consequences-and-Prevention.aspx]

-

Blencowe H, Lee Ac, Cousens S, Bahalim A, Narwal R, Zhong N, Chou D, Say L, Modi Northward, Katz J: Preterm birth associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global level for 2010. Pediatric Research. 2013

-

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi Grand, Flaxman Advertizing, Michaud C, Ezzati Thousand, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S: Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Affliction Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380: 2197-2223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-four.

-

Langhoff-Roos J, Kesmodel U, Jacobsson B, Rasmussen S, Vogel I: Spontaneous preterm commitment in primiparous women at low risk in Denmark: population based study. BMJ. 2006, 332: 937-939. 10.1136/bmj.38751.524132.2F.

-

Martin JA, Hamilton Exist, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Kirmeyer S, Osterman MJ: Births: terminal information for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010, 58: one-85.

-

Thompson JM, Irgens LM, Rasmussen S, Daltveit AK: Secular trends in socioeconomic status and the implications for preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006, 20: 182-187. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00711.x.

-

Hamilton Exist, Ventura P, Osterman M, Kirmeyer S, Mathews MS, Wilson E: Births: Terminal Data for 2009. National Vital Staistic Reports. 2011, lx:

-

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, Vera Garcia C, Rohde South, Say L, Backyard JE: National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with fourth dimension trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic assay and implications. Lancet. 2012, 379: 2162-2172. ten.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4.

-

WHO: WHO: recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal catamenia and utilise of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths. Modifications recommended by FIGO as amended October 14, 1976. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977, 56: 247-253.

-

Marlow N: Full term; an artificial concept. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012, 97: F158-x.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301507.

-

Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, Cousens S, Kumar R, Ibiebele I, Gardosi J, Mean solar day LT, Stanton C: Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the information count?. Lancet. 2011, 377: 1448-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(x)62187-3.

-

Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, Creanga AA, Tuncalp O, Balsara ZP, Gupta S: National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011, 377: 1319-1330. ten.1016/S0140-6736(10)62310-0.

-

Goldenberg RL, Nelson KG, Dyer RL, Wayne J: The variability of viability: the issue of physicians' perceptions of viability on the survival of very lowbirth weight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982, 143: 678-684.

-

Sanders MR, Donohue PK, Oberdorf MA, Rosenkrantz TS, Allen MC: Affect of the perception of viability on resources allocation in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 1998, xviii: 347-351.

-

Flenady 5, Middleton P, Smith GC, Knuckles Due west, Erwich JJ, Khong TY, Neilson J, Ezzati Yard, Koopmans L, Ellwood D: Stillbirths: the way forward in highincome countries. Lancet. 2011, 377: 1703-1717. ten.1016/S0140-6736(11)60064-0.

-

Kramer MS, Papageorghiou A, Culhane J, Bhutta Z, Goldenberg RL, Gravett One thousand, Iams JD, Conde-Agudelo A, Waller S, Barros F: Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm nascency syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 206: 108-112. x.1016/j.ajog.2011.x.864.

-

Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, Papageorghiou AT, Waller SA, Kramer One thousand, Culhane J, Barros F, Conde-Agudelo A, Bhutta ZA: The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a nomenclature organisation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012, 206: 113-118. 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865.

-

Steer P: The epidemiology of preterm labour. BJOG. 2005, 112 (Suppl 1): 1-3.

-

Menon R: Spontaneous preterm nascence, a clinical dilemma: etiologic, pathophysiologic and genetic heterogeneities and racial disparity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008, 87: 590-600. 10.1080/00016340802005126.

-

Plunkett J, Muglia LJ: Genetic contributions to preterm birth: implications from epidemiological and genetic association studies. Ann Med. 2008, 40: 167-195. 10.1080/07853890701806181.

-

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R: Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008, 371: 75-84. x.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4.

-

Muglia LJ, Katz M: The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. Due north Engl J Med. 2010, 362: 529-535. ten.1056/NEJMra0904308.

-

Blondel B, Macfarlane A, Gissler M, Breart M, Zeitlin J: Preterm birth and multiple pregnancy in European countries participating in the PERISTAT project. BJOG. 2006, 113: 528-535. ten.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00923.x.

-

Felberbaum RE: Multiple pregnancies after assisted reproduction - international comparison. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007, 53-lx. 15 Suppl 3

-

Blondel B, Kaminski M: Trends in the occurrence, determinants, and consequences of multiple births. Semin Perinatol. 2002, 26: 239-249. 10.1053/sper.2002.34775.

-

Kaprio J MR: Demographic trends in Nordic countries. Multiple Pregnancy: Epidemiology, Gestation & Perinatal Conditions 2nd edn. Edited past: Blickstein I KL. 2005, London: Taylor & Francis, 22-25. ii

-

Lim JW: The changing trends in live birth statistics in Korea, 1970 to 2010. Korean J Pediatr. 2011, 54: 429-435. 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.11.429.

-

Hamilton Be, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Osterman MJ: Births: concluding information for 2008. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010, 59: 1, three-71.

-

Gravett MG, Rubens CE, Nunes TM: Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (ii of 7): discovery science. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010, S2-10 Suppl ane

-

Lee SE, Romero R, Park CW, Jun JK, Yoon BH: The frequency and significance of intraamniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insuffi ciency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 198: 633 e631-638.

-

Zeitlin J, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, De Mouzon J, Rivera L, Ancel PY, Blondel B, Kaminski M: Fetal sexual practice and preterm birth: are males at greater risk?. Hum Reprod. 2002, 17: 2762-2768. 10.1093/humrep/17.x.2762.

-

Kent AL, Wright IM, Abdel-Latif ME: Bloodshed and adverse neurologic outcomes are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatrics. 2012, 129: 124-131. x.1542/peds.2011-1578.

-

Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM: Epidemiology of preterm nascence and its clinical subtypes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006, 19: 773-782. 10.1080/14767050600965882.

-

Patel RR, Steer P, Doyle P, Little MP, Elliott P: Does gestation vary by ethnic group? A London-based study of over 122,000 pregnancies with spontaneous onset of labour. Int J Epidemiol. 2004, 33: 107-113. x.1093/ije/dyg238.

-

Farrell PM, Wood RE: Epidemiology of hyaline membrane disease in the The states: analysis of national mortality statistics. Pediatrics. 1976, 58: 167-176.

-

Alexander GR, Kogan M, Bader D, Carlo W, Allen M, Mor J: Us birth weight/ gestational age-specific neonatal bloodshed: 1995-1997 rates for whites, hispanics, and blacks. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: e61-66. x.1542/peds.111.1.e61.

-

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Fuchs KM, Young OM, Hoff human MK: Nonspontaneous late preterm birth: etiology and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 205: 456 e451-456.

-

Mukhopadhaya N, Arulkumaran Due south: Reproductive outcomes after in-vitro fertilization. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007, xix: 113-119. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32807fb199.

-

Kalra SK, Molinaro TA: The association of in vitro fertilization and perinatal morbidity. Semin Reprod Med. 2008, 26: 423-435. 10.1055/s-0028-1087108.

-

Joseph KS, Demissie One thousand, Kramer MS: Obstetric intervention, stillbirth, and preterm birth. Semin Perinatol. 2002, 26: 250-259. 10.1053/sper.2002.34769.

-

Joseph KS, Kramer MS, Marcoux S, Ohlsson A, Wen SW, Allen A, Platt R: Determinants of preterm nascency rates in Canada from 1981 through 1983 and from 1992 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339: 1434-1439. 10.1056/NEJM199811123392004.

-

Barros FC, Velez Mdel P: Temporal trends of preterm nativity subtypes and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 107: 1035-1041. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000215984.36989.5e.

-

Alhaj AM, Radi EA, Adam I: Epidemiology of preterm birth in Omdurman Maternity hospital, Sudan. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010, 23: 131-134. 10.3109/14767050903067345.

-

Ip M, Peyman E, Lohsoonthorn V, Williams MA: A case-control written report of preterm commitment adventure factors according to clinical subtypes and severity. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010, 36: 34-44. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01087.x.

-

Nkyekyer K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Boafor T: Singleton preterm births in korle bu pedagogy hospital, accra, ghana-origins and outcomes. Ghana Med J. 2006, twoscore: 93-98.

-

Klebanoff MA, Shiono PH: Height down, bottom up and inside out: reflections on preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1995, 9: 125-129. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1995.tb00126.10.

-

Kramer MS, McLean FH, Boyd ME, Conductor RH: The validity of gestational age estimation by menstrual dating in term, preterm, and postterm gestations. JAMA. 1988, 260: 3306-3308. 10.1001/jama.1988.03410220090034.

-

ICD-x: international statistical classificiation of diseases and related health problems: 10th revision. second ed. [http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD-10_2nd_ed_volume2.pdf]

-

Froen JF, Gordijn SJ, Abdel-Aleem H, Bergsjo P, Betran A, Duke CW, Fauveau V, Flenady V, Hinderaker SG, Hofmeyr GJ: Making stillbirths count, making numbers talk-issues in data drove for stillbirths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009, 9: 58-x.1186/1471-2393-ix-58.

-

Annual Reports for the years 1991 and 1999. Melbourne:Consultative Council on Obstetrics and Paediatric Mortality and Morbidity, 1992 and 2001.

-

MRC PPIP Users, the Saving Babies Technical Task Squad: Saving Babies 2008-2009. 2010, 7th written report on perinatal intendance in South Africa

-

Miljeteig I, Johansson KA, Sayeed SA, Norheim OF: End-of-life decisions as bedside rationing. An upstanding analysis of life support restrictions in an Indian neonatal unit. J Med Ethics. 2010, 36: 473-478. 10.1136/jme.2010.035535.

-

Lumley J: Defining the problem: the epidemiology of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003, 110 (Suppl 20): iii-7.

-

Millennium, Development Goals Indicators. 2012, Accessed 3rd January, [http://mdgs.united nations.org/unsd/mdg/Default.aspx]

-

Katz J, Lee Air conditioning, Kozuki N, Lawn JE, Cousens S, Blencowe H, Ezzati Yard, Bhutta ZA, Marchant T, Willey BA: Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and centre-income countries: a pooled state assay. Lancet. 2013

-

Saigal S, Doyle LW: An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm nascency from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008, 371: 261-269. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1.

-

Mohangoo AD, Buitendijk SE, Szamotulska K, Chalmers J, Irgens LM, Bolumar F, Nijhuis JG, Zeitlin J: Gestational age patterns of fetal and neonatal mortality in europe: results from the Euro-Peristat project. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e24727-ten.1371/journal.pone.0024727.

-

Lawn JE, Davidge R, Paul VK, von Xylander Due south, de Graft Johnson J, Costello A, Kinney MV, Segre J, Molyneux 50: Born Too Soon: Care for the preterm baby. Reprod Health. 2013, 10 (Suppl 1): S5-ten.1186/1742-4755-ten-S1-S5.

-

Davidoff MJ, Dias T, Damus K, Russell R, Bettegowda VR, Dolan Southward, Schwarz RH, Greenish NS, Petrini J: Changes in the gestational age distribution among U.S. singleton births: impact on rates of tardily preterm birth, 1992 to 2002. Semin Perinatol. 2006, xxx: 8-15. ten.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.009.

-

Dean SV, Mason EM, Howson CP, Lassi ZS, Imam AM, Bhutta ZA: Born Too Soon: Care before and between pregnancy to forbid preterm births: from evidence to activeness. Reprod Health. 2013, 10 (Suppl ane): S3-x.1186/1742-4755-ten-S1-S3.

-

Requejo J, Althabe F, Merialdi K, Keller Chiliad, Katz J, Menon R: Built-in Besides Presently: Care during pregnancy and childbirth to reduce preterm deliveries and meliorate health outcomes of the preterm baby. Reprod Health. 2013, 10 (Suppl 1): S4-ten.1186/1742-4755-ten-S1-S4.

-

Kramer MS, Demissie Chiliad, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauve R, Liston R: The contribution of balmy and moderate preterm nativity to infant mortality. Fetal and Infant Wellness Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. JAMA. 2000, 284: 843-849. x.1001/jama.284.7.843.

-

Femitha P, Bhat BV: Early Neonatal Outcome in Late Preterms. Indian J Pediatr. 2011

-

Escobar GJ, Clark RH, Greene JD: Short-term outcomes of infants built-in at 35 and 36 weeks gestation: we need to ask more questions. Semin Perinatol. 2006, 30: 28-33. x.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.005.

-

Teune MJ, Bakhuizen S, Gyamfi Bannerman C, Opmeer BC, van Kaam AH, van Wassenaer AG, Morris JM, Mol BW: A systematic review of astringent morbidity in infants born late preterm. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 205: 374 e371-379.

-

Quigley MA, Poulsen One thousand, Boyle E, Wolke D, Field D, Alfi revic Z, Kurinczuk JJ: Early term and tardily preterm birth are associated with poorer school performance at historic period 5 years: a cohort study. Arch Dis Kid Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012

-

Woythaler MA, McCormick MC, Smith VC: Belatedly preterm infants have worse 24-month neurodevelopmental outcomes than term infants. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: e622-629. 10.1542/peds.2009-3598.

-

Petrou South, Eddama O, Mangham L: A structured review of the recent literature on the economic consequences of preterm nascency. Curvation Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011, 96: F225-232. ten.1136/adc.2009.161117.

-

Limburg H, Gilbert C, Hon do Northward, Dung NC, Hoang Thursday: Prevalence and causes of blindness in children in Vietnam. Ophthalmology. 2012, 119: 355-361. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.07.037.

-

Zepeda-Romero LC, Barrera-de-Leon JC, Camacho-Choza C, Gonzalez Bernal C, Camarena-Garcia East, Diaz-Alatorre C, Gutierrez-Padilla JA, Gilbert C: Retinopathy of prematurity as a major cause of astringent visual harm and incomprehension in children in schools for the blind in Guadalajara city, Mexico. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011, 95: 1502-1505. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300015.

-

Born Too Soon: The Global Activity Study on Preterm Birth. Edited by: Howson CP, Kinney MV, Lawn JE. 2012, March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the Children, World Wellness Organization. New York, [http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/preterm_birth_report/en/index1.html]

-

Keeping promises, measuring results: Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health.

-

Blencowe H, Cousens Due south, Chou D, Oestergaard MZ, Say L, Moller A, Kinney M, Backyard J: Affiliate ii: 15 one thousand thousand preterm births: Priorities for action based on national, regional and global estimates. Built-in Too Soon: the Global Activity Report on Preterm Birth. Edited past: Howson CP KM, Backyard JE. 2012, New York 2012: March of Dimes, PMNCH, Relieve the Children, World Health Organization, New York, [http://world wide web.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/borntoosoon_chapter2.pdf]

-

O'Connor AR, Wilson CM, Fielder AR: Ophthalmological problems associated with preterm birth. Eye (Lond). 2007, 21: 1254-1260. 10.1038/sj.center.6702838.

-

Marlow Due north, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, Samara M: Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm nascency. North Engl J Med. 2005, 352: nine-nineteen. ten.1056/NEJMoa041367.

-

Doyle LW, Ford Thousand, Davis Northward: Wellness and hospitalistions later belch in extremely low birth weight infants. Semin Neonatol. 2003, 8: 137-145. ten.1016/S1084-2756(02)00221-X.

-

Greenough A: Long term respiratory outcomes of very premature birth (<32 weeks). Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 17: 73-76. 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.009.

-

Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, Newton CR: Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012, 379: 445-452. x.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8.

-

Hagberg B, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Uvebrant P: Irresolute panorama of cognitive palsy in Sweden. VIII. Prevalence and origin in the birth year period 1991-94. Acta Paediatr. 2001, xc: 271-277.

-

Singer LT, Salvator A, Guo S, Collin 1000, Lilien L, Baley J: Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the nascency of a very low-birth-weight babe. JAMA. 1999, 281: 799-805. ten.1001/jama.281.9.799.

Acknowledgements

The Born Likewise Soon study was funded past March of Dimes, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Kid Health and Salve the Children. We would similar to thank the Built-in Likewise Soon Preterm Birth Activeness Grouping, including the Preterm Nascency Technical Review Panel and all the report authors (in alphabetical order): José Belizán (chair), Hannah Blencowe, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Sohni Dean, Andres de Francisco, Christopher Howson, Mary Kinney, Mark Klebanoff, Joy Backyard, Silke Mader, Elizabeth Mason (chair), Jeffrey Murray, Pius Okong, Carmencita Padilla, Robert Pattinson, Jennifer Requejo, Craig Rubens, Andrew Serazin, Catherine Spong, Antoinette Tshefu, Rexford Widmer, Khalid Yunis, Nanbert Zhong.

The authors appreciated review and inputs from Mark Klebanoff and Khalid Yunis. Thank you to Megan Bruno for her administrative support. Nosotros would also like to give thanks the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for funding the time for Boston Consulting Grouping.

This article has been published as part of Reproductive Wellness Volume ten Supplement 1, 2013: Born too soon. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.reproductive-wellness-periodical.com/supplements/10/S1.

Writer information

Affiliations

Consortia

the Born Besides Soon Preterm Birth Action group (see acknowledgement for full list)

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author'southward declare that they take no disharmonize of interest. The authors lone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they practice non necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Authors' contribution

HB, MK and JL drafted the paper with SC, DC, MZO, LS, ABM. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12978_2013_232_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Boosted file i: In line with the journal's open up peer review policy, copies of the reviewer reports are included as boosted file ane. (DOC 46 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is published nether license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Admission article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nothing/1.0/ ) applies to the data fabricated available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blencowe, H., Cousens, S., Chou, D. et al. Born Likewise Shortly: The global epidemiology of 15 one thousand thousand preterm births. Reprod Health 10, S2 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-x-S1-S2

Keywords

- Preterm birth

- epidemiology

- neonatal bloodshed

Source: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2

0 Response to "What Is the Earliest Gestational Age a Baby Can Be Born Without Risk of Major, Lifelong Disability?"

Post a Comment